Background: B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T-cell) therapy has exhibited remarkable efficacy in refractory or relapsed multiple myeloma (R/R MM), but recurrence and rapid progression of disease are still observed in some cases within a short time after treatment. Long-term pomalidomide therapy, which potentiates T-cell functionality and has direct antimyeloma effects, might enhance the efficacy of BCMA CAR-T-cell therapy. Here, we present the efficacy of this combination regimen for R/R MM.

Methods: We performed a single-center prospective clinical study that was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registration Center (ChiCTR2000036350). Patients with relpased or refractory multiple myeloma receiving BCMA CAR-T cell infusion were randomized to receive long-term pomalidomide treatment (4 mg/day) one month after infusion. The primary endpoint is overall survival (OS) in R/R MM with long-term pomalidomide administration compared to those without pomalidomide therapy after CAR T-cell infusion. The secondary endpoints include time to progression (TTP) and therapeutic response. Also, the copy numbers of CAR were assessed after infusion.

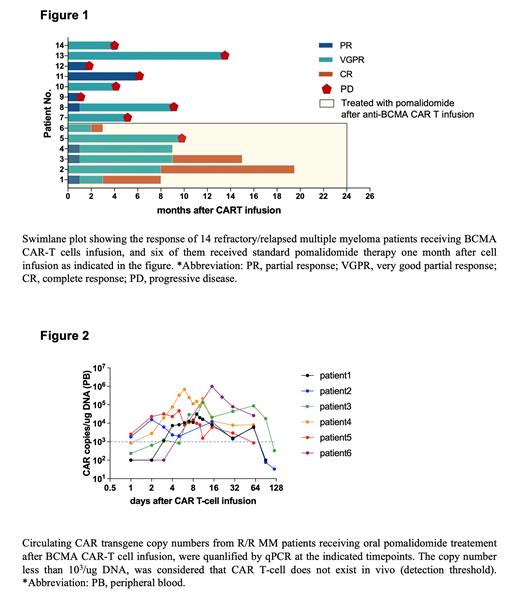

Results: A total of 14 R/R MM patients who received BCMA CAT T-cell therapy, were included in this study. The median age of the enrolled R/R MM patients was 59.5 years (44-71). Five patients had high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities (IGH rearrangement, 1q21 amplification, and P53 deletion) at the time of initial diagnosis. In addition, high-risk genetic alterations were newly detected in patient 2 during first-line therapy. All patients had previously received 3 to 6 lines of treatment with proteasome inhibitors (PIs), immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), or anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies. As shown in Figure 1, all patients had demonstrated progressive disease prior to CAR T-cell infusion. The objective response rate (ORR) of BCMA-CART was 100%. Three months following CAR-T-cell infusion, of the 6 patients receiving pomalidomide, all patients (6/6) achieved VGPR (very good partial response) or CR (complete response), while only 5 patients (5/8) who did not receive pomalidomide treatment achieved VGPR or better. At a median follow-up of 19.7 months, for the 8 patients who did not receive pomalidomide administration, the median TTP (time to progression) was 4.5 (1-14) months, while the TTP was not reached in patients who received long-term pomalidomide treatment.

Moreover, the dynamic abundance of circulating BCMA CAR-T cells was monitored as shown in Figure 2. In patients who received pomalidomide treatment after CAR-T-cell therapy, the CAR copy numbers of circulating CAR-T cells peaked 8 to 10 days after CAR-T-cell infusion, with a peak copy number of up to 10 6. In addition, BCMA CAR-T cells persisted (>1*10 3 copies/µg DNA) for 3 months in vivo. Without pomalidomide administration, BCMA CAR-T cells persisted for up to 2.5 months in the peripheral circulation (results not shown).

Conclusion: Our results confirm the efficacy of the long-term oral pomalidomide administration (4 mg/day) after BCMA CAR T-cell infusion in patients with R/R MM. Notably, this combination regieme reduced the recurrence rate and prolonged progression-free survival for R/R MM patients, providing a promising option for treating R/R MM. In addition, oral administration of pomalidomide did not significantly prolong the persistence of BCMA CAR T-cells in vivo. However, data from studies with larger sample sizes are required to draw valid conclusions.

Disclosures

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal